Public transport in Auckland

| Auckland Transport (AT) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

An AT AM class train at Parnell station | |||

| Overview | |||

| Area served | Auckland metropolitan area | ||

| Locale | Auckland region | ||

| Transit type | Suburban rail, bus, ferry | ||

| Annual ridership |

| ||

| Website | at | ||

| Operation | |||

| Operator(s) | Auckland One Rail Bayes Coachlines Kinetic Group (Go Bus, NZ Bus) Howick and Eastern Buses Pavlovich Transport Solutions Ritchies Transport Tranzit Group (Tranzurban Auckland) Belaire Ferries Explore Group Fullers360 (Waiheke Bus Company) SeaLink NZ | ||

| |||

Public transport in Auckland, the largest metropolitan area of New Zealand, consists of three modes: bus, train and ferry. Services are coordinated by Auckland Transport (AT) under the AT and AT Metro brands. Waitematā railway station is the main transport hub.

Until the 1950s, Auckland was well served by public transport and had high levels of ridership.[2] However, the dismantling of an extensive tram system in the 1950s, the decision by Stan Goosman[3] to not electrify Auckland's rail network, and a focus of transport investment into a motorway system led to the collapse in both mode share and total trips.[4] By the 1990s, Auckland had experienced one of the sharpest declines in public transport ridership in the world, with only 33 trips per capita per year.[5]

Since 2000, a greater focus has been placed on improving Auckland's public transport system through a series of projects and service improvements. Major improvements include the Waitematā railway station, the Northern Busway, the upgrade and electrification of the rail network[6] and the introduction of integrated ticketing through the AT HOP Card. These efforts have led to sustained growth in ridership, particularly on the rail network. Between June 2005 and November 2017 total ridership increased from 51.3 million boardings per annum to 90.9 million.[7]

Despite those strong gains, the overall share of travel in Auckland by public transport is still quite low. At the 2013 census, around 8% of journeys to work were by public transport[8] and per capita ridership in 2017 of around 55 boardings is still well below that of Wellington, Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and most large Canadian cities.[9]

Auckland's rapid population growth means that improving the city's public transport system is a priority for Auckland Council[10] and the New Zealand Government.[11] Major improvements planned or underway include the City Rail Link,[12] construction of the Eastern Busway between Panmure and Botany, and the proposed City Centre–Māngere Line, a light rail line between the city centre and Auckland Airport,[13] which was cancelled by the coalition government in 2024.[14]

History

[edit]Pre World War II growth

[edit]Horse-drawn trams operated in Auckland from 1884. The Auckland Electric Tram Company's system was officially opened on 17 November 1902.[15] The Electric Tram Company started as a private company before being acquired by Auckland City Council. The tram network enabled and shaped much of Auckland's growth throughout the early 20th century. Auckland's public transport system was very well utilised, with usage peaking at over 120 million boardings during the Second World War, when Auckland's population was less than 500,000.[16]

Post World War II decline

[edit]Auckland's extensive tram network was removed in the 1950s, with the last line closing in late 1956.[17][18] Although a series of ambitious rail schemes were proposed between the 1940s and 1970s,[19] the focus of transport improvements in Auckland shifted to developing an extensive motorway system. Passionate advocacy from long-time Mayor of Auckland City Council Dove-Myer Robinson for a "rapid rail" scheme was ultimately unsuccessful.[20]

Removal of the tram system, little investment in Auckland's rail network and growing car ownership in the second half of the 20th century led to a collapse in ridership across all modes of public transport.[4] From a 1954 average level of 290 public transport trips per person per year (a share of 58% of all motorised trips), patronage decreased rapidly.[9][21] 1950s ridership levels were only reached again in the 2010s, despite Auckland's population growing four-fold over the same time period.[4]

These decisions also shaped Auckland's growth patterns in the late 20th century, with the city becoming a relatively low-density dispersed urban area with a population highly dependent on private vehicles for their travel needs.[22] By the late 1990s ongoing population growth and high levels of car use were leading to the recognition that traffic congestion was one of Auckland's biggest problems.[23]

Privatisation

[edit]It has been claimed that the city's public transport decline resulted from, "privatisation, a poor regulatory environment and a funding system that favours roads".[24] On the other hand, NZ Bus claim that increasing passengers and cost control began with privatisation in 1991.[25]

21st century revival

[edit]As concerns over urban sprawl and traffic congestion grew in the 1990s and early 2000s, public transport returned to the spotlight, with growing agreement of the "need for a substantial shift to public transport".[26] Growing recognition that Auckland could no longer "build its way out of congestion" through more roads alone led to the first major improvements to Auckland's public transport system in half a century:

- Waitematā station was opened in 2003 as Britomart Transport Centre, the first major upgrade of Auckland's rail network since World War II. This project allowed trains to reach into the heart of Auckland's city centre and acted as a catalyst for the regeneration of this part of downtown Auckland.[27]

- The Northern Busway was opened in 2008, providing Auckland's North Shore with rapid transit that enabled bus riders to avoid congestion on the Northern Motorway and Auckland Harbour Bridge.[28]

- A core upgrade of Auckland's rail network between 2006 and 2011, known as Project DART, which included double-tracking of the Western Line, the reopening of the Onehunga Branch line to Onehunga, a rail spur to Manukau City and a series of station upgrades.[29]

- Electrification of the Auckland rail network (except for the section of track between Papakura and Pukekohe) and the purchase of new electric trains from Spanish manufacturer CAF. Electric train services commenced in 2014. AT trains were 100% electric in 2022.[30]

- Implementation of an integrated ticketing and fares system, through the AT HOP card, enabling consistent fares and easy transfers between different bus, train and ferry operators.

- Electric AT buses and depots began replacing diesel in 2020. In March 2024 there were 138 zero-emission buses, including one double-decker.[31][32][33]

Despite these improvements, the lack of investment in Auckland's public transport system throughout the latter part of the 20th century means the city still has much lower levels of ridership than other major cities in Canada and Australia.[34] Auckland's ongoing strong population growth and constrained geography means that Auckland's transport plans now have a strong focus on further improving the quality and attractiveness of public transport.[35] Further improvements are to be realised in the years to 2028 under the Auckland Transport Alignment Project (ATAP), valued at NZ$28 billion[36] ($4.6 billion more than previously planned), of which $9.1 billion is for additional public transport projects, including: the completion of the City Rail Link; the construction of the Eastern Busway, which will run from Panmure to Botany; Northern Busway extension to Albany; the extension of the railway electrification to Pukekohe; a third line to Auckland between Westfield and Wiri[37] or Wiri and Papakura, to allow freight trains to bypass stationary passenger trains;[38] further new electric trains and the construction of a new light rail line, the City Centre–Māngere Line.[39]

In late January 2022, the New Zealand Government approved a NZ$14.6 billion project to establish a partially tunneled light rail network between Auckland Airport and the Wynyard Quarter in the Auckland CBD. The proposed light rail network will integrate with current train and bus hubs as well as the City Rail Link's stations and connections. Transport Minister Michael Wood also added that the Government would decide on plans to establish a second harbour crossing at Waitematā Harbour in 2023.[40][41]

Buses

[edit]

Urban services

[edit]

Buses provide for around 70% of public transport trips in Auckland.[7] Bus services generally run from around 6am to midnight, with a limited number of buses linking Auckland's suburbs and city centre after midnight on Friday and Saturday nights only, with Northern Express services on the Northern Busway on the North Shore running half-hourly until 3:00 a.m.[42] Services are contracted by Auckland Transport (AT) and operated by a number of private companies, including:

- Bayes Coachlines

- Go Bus

- Howick & Eastern Buses

- NZ Bus

- Pavlovich Transport Solutions

- Ritchies Transport

- Tranzurban Auckland (Tranzit Group) – contracted operator of NX2 services on the Northern Busway[43]

- Waiheke Bus Company (by Fullers, 5 routes)

AT began rebranding bus services to AT Metro in 2014–2015 to create a single identity for all bus services, with some exceptions like the Link buses which retained their red, green and orange colours.[44] In 2023, AT began decommissioning the AT Metro brand, replacing it with the refreshed AT brand identity. The livery colours are being retrained.[45][46]

There are five Link services; all accept fare payment by AT HOP card or cash and all run from early morning to late evening, 7 days of the week.[47]

- CityLink – red electric buses; Wynyard Quarter – Queen Street – Karangahape Road

- InnerLink – green buses – both way loop; Waitematā – Parnell – Newmarket – Karangahape Road – Ponsonby Road – Victoria Park – Waitematā.

- OuterLink – amber buses – both way loop; Wellesley Street – Parnell – Newmarket – Mount Eden – Mount Albert – Westmere – Herne Bay – Wellesley Street.

- TāmakiLink – blue electric buses; Waitematā – Spark Arena – Kelly Tarlton's Sea Life Aquarium – Mission Bay – Kohimarama Beach – St Heliers Bay – Glen Innes.

- AirportLink – orange electric buses; Manukau – Puhinui – Auckland Airport

Airport services

[edit]The AirportLink bus provides a connection to Puhinui railway station where Southern Line or Eastern Line services connect from Waitematā in downtown Auckland. It also serves Manukau railway station to provide connections to the east. Bus 38 connects the Airport to Māngere and Onehunga.[48]

The SkyDrive bus provides a direct bus connection between Auckland Airport and Auckland CBD.[49] Previously, SkyBus provided direct bus services, however the service ceased due to the Covid-19 pandemic.[50]

Bus priority facilities

[edit]

Auckland has a growing number of bus lanes, some of which operate at peak times only and others 24 hours a day. These lanes are for buses and two-wheeled vehicles only and are intended to reduce congestion and shorten travel times. All are sign-posted and marked on the road surface.

The Central Connector bus lane project improved links between Newmarket and the inner city, while bus lanes are also planned on Remuera Road and St Johns Road to connect the city with the Eastern Bays suburbs.

The Northern Busway provides complete separation for buses from general traffic between Akoranga busway station (near Takapuna) and Albany busway station. In the near future, a new station will be built between Albany and Constellation busway station called Rosedale. It will serve the nearby Industrial Area. [51] In the long-term plans remain to extend the busway to Hibiscus Coast busway station, and Orewa.[52]

The Eastern Busway (AMETI) is currently being constructed to connect Botany and Panmure with a separated busway along Ti Rakau Drive, onto Pakuranga Road and Lagoon Drive. Pre-construction began in late 2018, with the removal of houses along Pakuranga Road due to be complete by April 2019. Stage one connecting Panmure and Pakuranga opened in 2021, with continued construction of the busway from Pakuranga to Botany being completed by 2025. A new Botany station is due to be completed by 2026. Further extensions to Auckland Airport via Manukau City are being explored, although no decisions on this extension have been made public.[citation needed]

Other planned busways include the Northwestern Busway[53] between Westgate and the city centre (possibly to be built as light-rail instead of a busway[11]) and a bus connection between Auckland Airport, Manukau City and Botany.[11] There are currently small sections of bus lanes on SH16 between Westgate and Newton Rd as an interim "short-term" improvement before the Northwestern Busway is built.[54]

Commuter services

[edit]At peak hours express buses serve commuters from the outlying towns north and south of Auckland.

Express bus 125X took up to 2 hours[55] to cover the 43 km (27 mi) from Helensville to Auckland. However, this route is no longer operated since November 2023 as part of a West Auckland network change.

Mahu City Express has run a commuter bus from Snells Beach to Parnell[56] since October 2015. It runs twice a day, Monday to Friday, taking about an hour[56] for the 57 km (35 mi) from Warkworth to Victoria Park,[57] with stops at Smales Farm and Akoranga.[56] Since 1 March 2021 the first electric luxury coach in the country has been on the route.[58] It uses a 40-seat Yutong TCe12, bought with the aid of a $352,500 EECA grant.[59]

Bus 995 runs hourly, linking Warkworth to Hibiscus Coast busway station,[60] with connection to the Northern Express, taking a bit over an hour to Auckland.[61]

Waiuku's bus 395 links it to Papakura railway station twice a day.[62]

Long-distance services

[edit]Long-distance bus operator InterCity links Auckland with all the main centres in the North Island,[63] also operating the budget-orientated SKIP Bus services.[64] Skip buses were suspended from 25 March 2020.[65] Until 18 August 1996 InterCity services operated from Auckland railway station. Since then they have run from SkyCity.[66] SkyCity wants the bus station to move and it has been criticised for diesel fumes and poor toilets.[67] However, InterCity rejected a move to Manukau and, in 2020, plans to move back to the old railway station were dropped.[68]

Night services

[edit]There are a total of 15 routes as part of the Night Bus and Northern Express bus services which operate on Friday and Saturday nights between the hours of 00:00 and 03:30.[69][70] Most routes depart the city centre on an hourly basis although the Northern Express bus route NX1 is more frequent.[69] The night bus services were paused during COVID but returned on 2 December 2021 when AT's Group Manager Metro Services Stacey van der Putten noted that AT was "bringing back a wide range of our 'Night Buses' services this weekend to help support our city's hospitality sector and to make it easier for town-goers and hospitality workers alike to get home safely and affordably in the early hours."[71]

Busiest routes

[edit]The following table shows the 20 busiest bus routes in Auckland by boardings in 2023.[72]

| Rank | Route | Description | Annual patronage (2023) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NX1 | Hibiscus Coast Station to Britomart via Northern Busway. One of two Northern Express services. | 3,770,829 |

| 2 | 70 | Botany to Britomart via Pakuranga, Panmure, and Ellerslie | 3,637,401 |

| 3 | NX2 | Albany Station to City universities via Northern Busway. One of two Northern Express services. | 2,419,166 |

| 4 | OUT | Outer Link: Wellesley St, Parnell, Newmarket, Mountt Eden, Saint Lukes, Point Chevalier, Westmere, Wellesley St | 1,912,971 |

| 5 | 75 | Glen Innes to Wynyard Quarter via Remuera Road | 1,512,735 |

| 6 | INN | Inner Link: Britomart, Parnell, Newmarket, Karangahape Road, Ponsonby, Britomart | 1,480,555 |

| 7 | 18 | New Lynn to City Centre via Great North Road | 1,411,332 |

| 8 | 30 | Onehunga to City Centre via Manukau Road | 1,297,167 |

| 9 | 25B | Blockhouse Bay to City Centre via Dominion Road | 1,037,158 |

| 10 | 25L | Lynfield to City Centre via Dominion Road | 999,425 |

| 11 | 33 | Papakura to Ōtāhuhu via Great South Road | 874,883 |

| 12 | 83 | Albany to Takapuna via Browns Bay and Constellation station | 847,337 |

| 13 | 66 | Sylvia Park to Point Chevalier via Royal Oak and Mt Albert | 843,119 |

| 14 | 27W | Waikowhai to City Centre via Oakdale Road and Mount Eden Road | 810,532 |

| 15 | 24B | New Lynn to City Centre via Blockhouse Bay and Sandringham Road | 805,524 |

| 16 | 27H | Waikowhai to City Centre via Hillsborough Road and Mount Eden Road | 753,950 |

| 17 | CTY | City Link: Wynyard Quarter to Karangahape Road via Queen St | 726,372 |

| 18 | 22R | Rosebank Road to City Centre via New North Road | 692,586 |

| 19 | 24R | New Lynn to City Centre via Richardson Road and Sandringham Roadd | 690.807 |

| 20 | 120 | Henderson to Constellation Station via Upper Harbour Bridge | 658,109 |

Trains

[edit]

Urban services

[edit]Auckland's urban train services are operated under the AT brand by Auckland One Rail. Trains and stations are owned by Auckland Transport, while tracks and other rail infrastructure are owned by KiwiRail.

Since the opening of Waitematā railway station, significant improvements have been made to urban rail services. These include:

- Sunday services were reintroduced in October 2005 for the first time in over 40 years, together with a general 25% service frequency increase.[73]

- Project DART upgraded the core rail network between 2006 and 2012, including double-tracking the Western Line, completed in 2010,[74] constructing the Manukau Branch line from Wiri to Manukau City Centre, completed in 2012, rebuilding and reconfiguring Newmarket railway station, completed in 2010, and reopening the disused Onehunga Branch line for passengers[75] in September 2010.

- Electrification of the rail network from Swanson station on the Western Line and Papakura station on the Southern Line and the purchase of 57 electric trains. The first passenger services operated in April 2014.[76]

- Otahuhu railway station was extensively rebuilt to connect with a new bus interchange being built alongside. In October 2016, the interchange was opened to coincide with the launching of a new bus network timetable in South Auckland, Pukekohe and Waiuku.[77]

- The new Manukau bus station (next to Manukau railway station) was officially opened in April 2018 and bus services from the new facility began, serving South and East Auckland.[78][79]

- A bus and rail interchange at Puhinui connecting Auckland Airport to and from Manukau bus station, that began its construction of the first stage in October 2019 and completed in early 2021. The new interchange opened on 26 July 2021.[80][81][82]

These improvements have led to rapid growth in rail ridership, from a low of 1 million annual boardings in 1994 to over 20 million in 2017.[83] Increasing train frequencies to meet further growth is not possible because of the "dead end" at Waitematā railway station which means all trains entering and exiting the station need to use the same two tracks. The City Rail Link project, due to be opened in 2024 is a tunnel between Waitematā station and Maungawhau railway station designed to address these constraints, provide greater route flexibility across the entire network, and create a more direct route for Western Line services.[84] This project will convert the system from a commuter rail network to an S-Train network, providing metro-like frequencies during peak.

Services

[edit]There are four commuter rail lines:[85][86][87]

| Line | Frequency | Calling at | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Off-peak | ||||

| Eastern Line | 6 tph | 3 tph | Waitematā, Ōrākei, Meadowbank, Glen Innes, Panmure, Sylvia Park, Ōtāhuhu, Middlemore, Papatoetoe, Puhinui, Manukau | ||

| Southern Line | 6 tph | 3 tph | Waitematā, Parnell, Newmarket, Remuera, Greenlane, Ellerslie, Penrose, Ōtāhuhu, Middlemore, Papatoetoe, Puhinui, Homai, Manurewa, Te Mahia, Takaanini, Papakura, |

||

| Western Line | 6 tph | 3 tph | Waitematā, Parnell, Newmarket, Grafton, |

Trains reverse at Newmarket | |

| Onehunga Line | 2 tph | Newmarket, Remuera†, Greenlane†, Ellerslie, Penrose, Te Papapa, Onehunga | |||

| tph = trains per hour † station served at evenings only Maungawhau station is closed until 2024 for City Rail Link construction. | |||||

Rolling stock

[edit]| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Number | Carriages | Routes operated | Built | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km/h | mph | |||||||

| AM class |

|

EMU | 110 | 68 | 72 | 3 | Eastern Line Onehunga Line Southern Line (Waitematā–Papakura) Western Line |

2013–2020 |

Long-distance services

[edit]Auckland has two long-distance passenger train services. The first is the Northern Explorer to Wellington, operated by KiwiRail Scenic Journeys, which runs southbound on Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays and northbound Tuesdays, Fridays and Sundays. The service is mainly tourist-oriented.

The second is the Te Huia regional service, which runs one morning and one afternoon service each way between Hamilton and Auckland via The Base and Huntly.[88] This service was extended from its initial northern termini of Papakura railway station to Puhinui railway station and The Strand Station in January 2022.[89]

Future upgrades

[edit]A number of upgrades and extensions to the rail network have been proposed, some for several decades:

- From 13 August 2022, KiwiRail will be redeveloping Pukekohe station and the rail line to allow for Auckland Transport’s electric trains to travel between Pukekohe and Papakura. Pukekohe Station will close and the Pukekohe train service will be suspended until late 2024.[90]

- The Auckland Airport Line, an extension of the Onehunga Branch line to Auckland Airport over the Māngere Bridge

- An airport link from the North Island Main Trunk line at Manukau City, in addition to or instead of a link via Māngere Bridge

- Extension of electrification to Pukekohe (including new stations at Drury Central, Drury West and Paerata[91]), and eventually to Hamilton, although the Te Huia commuter train introduced in 2020 is diesel-hauled.[92][93]

- The Avondale-Southdown Line, a line between Avondale in west Auckland and the Southdown Freight Terminal, to allow freight trains to avoid Newmarket and reduce delays for both freight and passenger trains[94]

- A Third Main Line between Wiri and Westfield to allow freight trains to bypass stationary passenger trains on that section[95]

- Extension of rail across Waitematā Harbour to the North Shore[96] and possible conversion of the Northern Busway to light rail[11]

In 2020, the government announced funding for electrification of the railway line from Papakura to Pukekohe, new railway stations at Drury, a third main line and improvements to the Wiri – Quay Park corridor.[97]

In 2022, AT announced 23 new electric commuter trains would be added to its fleet, taking it to 95 in total.[98]

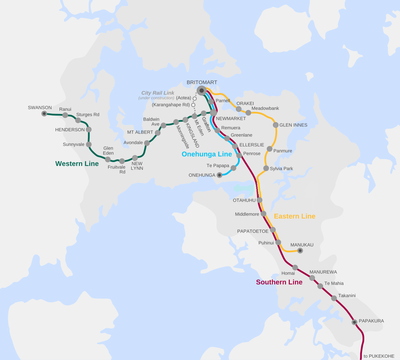

Network map

[edit]

Ferries

[edit]

History

[edit]The first official ferry started in 1854, the first steam ferry in 1860,[99] the first scheduled ferry in 1865, Auckland & North Shore Steam Ferry Co in 1869, Devonport Steam Ferry Company in 1885, a vehicle ferry in 1911 and North Shore Ferries in 1959.[100]

In 1981 George and Douglas Hudson bought North Shore Ferries and Waiheke Shipping Co. In 1984 they founded Gulf Ferries, and their first catamaran, the $3m Quickcat, cut the Waiheke ferry time from 75 minutes to 40,[101] with Fullers putting Kea on the Devonport route from 1988.[100] Fullers Corporation was mainly operating cruises and, in 1987, when they introduced Supercat III,[102] they were refused a licence to compete on Waiheke commuter trips.[103] The Hudsons bought Fullers from its 1988 receivership[104] and formed Fullers Group Ltd in 1994 and Stagecoach took a majority holding in 1998.[105] In 2009, Souter Holdings purchased Fullers Group and also 360 Discovery Cruises.[106]

In 2022, Auckland Transport (AT) purchased four diesel ferries that were in dire need of repair from Fullers, and is upgrading them to reduce their emissions.[107][108] There are plans to commission five new electric and hybrid-electric ferries, with the first two expected to arrive in 2024.[109][110]

Services

[edit]Around 7 million ferry trips per year[7] were made in Auckland in prior to COVID-19. Yearly patronage decreased to 3 million in 2021,[7] due to the ongoing impact of COVID-19 on public transport.

Most ferry routes start from Downtown Auckland and have no intermediate stops. The ferry operators are:

- Fullers360

- SeaLink

- Belaire (West Harbour and Rakino Island)[111]

- Explore (Tiritiri Matangi Island, Bayswater and Birkenhead / Northcote Point)[112][113]

Terminals

[edit]The Auckland Ferry Terminal is in downtown Auckland on Quay Street, between Princes Wharf and the container port, directly opposite Waitematā railway station.

- North Shore terminals: Devonport, Bayswater, Northcote Point, Birkenhead, Beach Haven, Gulf Harbour

- East Auckland terminals: Half Moon Bay, Pine Harbour

- Waitematā Harbour's western terminals: West Harbour, Hobsonville

Ferries also connect the city with islands of the Hauraki Gulf. Regular sailings serve Waiheke Island, with less frequent services to Great Barrier Island, Rangitoto Island, Motutapu Island and other inner-gulf islands, primarily for tourism.

There are no ferry services on the west coast of Auckland, although there were some historical services from Onehunga. None are planned, as the city's waterfront orientation is much stronger towards the (eastern) Waitematā Harbour than to the (western) Manukau Harbour.

Ticketing and fares

[edit]An integrated ticketing / smartcard system, known as the AT HOP card, was developed for Auckland by Thales, similar to systems like Octopus card in Hong Kong.[114][115]

The first stage of integrated ticketing came online in time for the Rugby World Cup 2011, with construction works for the 'tag on' / 'tag off' infrastructure having begun in January 2011.[116] The 'HOP Card' was publicised with a $1 million publicity campaign that started in early 2011.[115]

The AT HOP card system went live in October 2012 for trains, November 2012 for ferries and between June 2013 and March 2014 for buses.[117]

In 2016, Auckland Transport simplified fares by changing to a system based on 13 fare zones. The fare is no longer based on the distance travelled (number of stages), but on the number of zones passed through, so that a journey in a zone that involves multiple rides or even a mode mix (bus or train) will be charged only one fare.[118] Ferries are not included in the simplified fares system and are charged per ride.

A national ticketing system (branded as Motu Move) has been proposed by Waka Kotahi which will "improve public transport for New Zealanders through a standardised approach to paying for public transport which will provide a common customer experience no matter where you are in the country." Auckland is set to receive the system by 2026.[119]

In 2023, AT announced bus, train and ferry passengers would be able to 'tag on/off' with contactless payments (debit/Credit cards, Apple Pay and Google Pay) in addition to AT HOP cards by June 2024.[120] However, this has been delayed to late 2024.[121]

By 2028, AT HOP cards will have been fully replaced by Motu Move prepaid cards and contactless payments.[121]

Public advocacy

[edit]A number of groups advocate for improving public transport in Auckland. Some groups operate prominent blogs, participate in public discussions on social media and prepare plans advocating for particular improvements. These groups include:

- Greater Auckland[122]

- Campaign for Better Transport[123]

- Public Transport Users Association[124]

- Generation Zero

See also

[edit]- List of Auckland railway stations

- Public transport in New Zealand

- Rail transport in New Zealand

- Transport in Auckland

- Trolleybuses in Auckland

- Light rail in Auckland

References

[edit]- ^ "AT Metro patronage report". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ "Public transport patronage the highest in more than 60 years". OurAuckland. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Sir Dove-Myer Robinson on his Rapid Transit Scheme – Part 4". transportblog.co.nz. 18 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ a b c "Michael Lee: Sins of the fathers – legacy of harbour bridge". The New Zealand Herald. 1 June 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Mees, Paul (February 2001). "The American Heresy: Half a century of transport planning in Auckland".

- ^ "Developing Auckland's Rail Transport – DART". KiwiRail. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Auckland Transport Patronage Report".

- ^ "Journey to Work Patterns in the Auckland Region | Ministry of Transport". transport.govt.nz. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ a b Auckland's Transport Challenges Archived 25 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine (from the Draft 2009/10-2011/12 Auckland Regional Land Transport Programme, Page 8), ARTA, March 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- ^ "Mayor Phil Goff's vision for Auckland". Auckland Council. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d Orsman, Bernard (6 August 2017). "Jacinda Ardern outlines Labour's light rail plan for Auckland". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Nine millionth rail passenger arrives at Britomart". The New Zealand Herald. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ Auckland Transport (24 March 2017). "Airport and Mangere Rail".

- ^ "Government Cancels Auckland Light Rail". Simeon Brown, Minister for Transport, Beehive. 14 January 2024. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Tramway". Motat Museum of Transport and Technology. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "More PT ridership milestones – Greater Auckland". Greater Auckland. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Auckland Tram – Number 11 Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine (from the MOTAT website)

- ^ A Wheel on Each Corner, The History of the IPENZ Transportation Group 1956–2006 – Douglass, Malcolm; IPENZ Transportation Group, 2006, Page 12

- ^ @AmeliaJWade, Amelia Wade Reporter, NZ Herald amelia wade@nzherald co nz (31 May 2016). "Rail Link 100 years in the making". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ History of Auckland City – Chapter 4 Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (from the Auckland City Council website. Retrieved 7 June 2008.)

- ^ Mees, Paul (December 2009). Transport for Suburbia: Beyond the Automobile Age. Earthscan Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84407-740-3.

- ^ Ministry of Transport. "Auckland Transport Alignment Project – Foundation Report" (PDF).

- ^ Auckland City Council. "Central Transit Corridor Project". Archived from the original on 22 May 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- ^ "Why Is Auckland's Public Transport System So Poor? | Scoop News". scoop.co.nz. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "NZ Bus" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 February 2013.

- ^ Dearnaley, Mathew (23 April 2007). "Force people out of cars, says Treasury". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "Britomart – Auckland | Ministry for the Environment". mfe.govt.nz. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Busway FAQ on North Shore City Council website. Retrieved 11 January 2008

- ^ KiwiRail. "DART – KiwiRail". kiwirail.co.nz. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Transport, Auckland (18 March 2024). "Mission Electric". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Transport, Auckland (18 March 2024). "Mission Electric". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Auckland Mayor Wayne Brown powers up to drive electric bus round cones". NZ Herald. 13 April 2024. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Business.Scoop » Auckland Transport Welcomes First Double Decker Electric Bus". Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Wallis, Ian (15 August 2011). "Auckland Passenger Transport Performance Benchmark Study" (PDF).

- ^ "Auckland Transport Alignment Project | Ministry of Transport". transport.govt.nz. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "What you need to know about the $28b Auckland Transport Alignment Project". Stuff.co.nz. 26 April 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ "Wiri to Westfield – The Case for Investment" (PDF). KiwiRail. December 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "Jacinda Ardern outlines Labour's light rail plan for Auckland". Stuff. 6 August 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "Auckland Transport Alignment Project" (PDF). Auckland Council. April 2018.

- ^ Small, Zane (28 January 2022). "$14 billion Auckland light rail bid gets green light, decision on second Waitemata Harbour crossing on 2023". Newshub. Archived from the original on 29 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Auckland light rail tunnel to run to Mt Roskill before following SH20 to the airport". Radio New Zealand. 29 January 2022. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "Northern Express" (PDF). Auckland Transport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ "About Us | Tranzurban". Tranzurban. 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

Tranzurban is the newest addition to Tranzit Group and will operate a part of the new North Shore bus network from September 2018 in collaboration with Auckland Transport.

- ^ "AT Metro brand makes its debut". Auckland Transport. 16 December 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ Transport, Auckland (3 March 2024). "Brand identity guidelines". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand's first fully electric bus depot unveiled". Intelligent Transport. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Link bus service". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ "Airport Services". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ^ Granville, Alan (1 May 2022). "Welcome to New Zealand, here's how to escape the airport". Stuff. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Brooks, Sam (17 December 2021). "Alert: There is no airport bus service in Auckland or Wellington". The Spinoff. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Northern Corridor Newsletter – August 2015 21 August 2015" (PDF). New Zealand Transport Agency. 21 August 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ Transport, Auckland. "Supporting growth in the north". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ @BernardOrsman, Bernard Orsman Super City reporter, NZ Herald bernard orsman@nzherald co nz (15 September 2016). "Northwestern busway to get green light". The New Zealand Herald. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Transport, Auckland. "Northwestern Bus Improvements". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "Western Bus Timetable" (PDF). AT. 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c "Luxury Commuting On eCoaches. Round-Trip Bus From Auckland to Warkworth". Mahu City Express. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "Victoria Park to Warkworth". Google maps. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "Mahu City Express launches electric coach service". Local Matters. 22 February 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "Herald of the Future – Mahu City Express, NZ". BusNews.com.au. 21 April 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "Warkworth Kowhai Coast Wellsford Northern Bus Timetable" (PDF). AT. 13 October 2019.

- ^ "Journey planner". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ "Southern Bus Timetable" (PDF). AT. 25 July 2021.

- ^ Bookings (from the InterCity website. Retrieved 16 February 2008.)

- ^ "New budget coach service, Skip, hits North Island roads". New Zealand Herald. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "COVID-19 Updates". Entrada Travel Group. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "InterCity NZ". Facebook. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Auckland's Wonderful Long-Distance Bus Terminal". Greater Auckland. 24 February 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Contested plan for bus terminal on Auckland Māori land dropped". Stuff. 3 April 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Night bus". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "Night Bus. Fri & Sat Nights (Effective from August 2019)" (PDF). Auckland Transport. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "AT brings back Night Buses to support the city's hospitality sector". Auckland Transport. 2 December 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ "AT Metro bus performance report – January 2023 to December 2023". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Dearnaley, Mathew (11 October 2005). "Sunday trains come back to Auckland". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 12 January 2011.

- ^ "Auckland's rail renaissance". Region Wide. Auckland Regional Council. July 2010. p. 3.

- ^ Dearnaley, Mathew (14 March 2007). "Delight at Government's decision to reopen Onehunga line". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ "'Stunning' electric trains launched – but soon face delays". The New Zealand Herald. 27 April 2014. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Otahuhu's new transport hub the 'way to go' – Goff". 29 October 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- ^ "$49m bus station opens in Manukau". RNZ News. 7 April 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ^ "Manukau's new bus station opens". Auckland Transport. Archived from the original on 14 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ "Airport to Botany Rapid Transit". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ "Puhinui Station set for reopening with stunning design". Auckland Transport. 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Puhinui Station reopens Monday 26th July 2021". Auckland Transport. 27 July 2021.

- ^ "Auckland train patronage anticipated to hit 60 million". Stuff. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Pukekohe to Huapai rail line suggested". The New Zealand Herald. 27 February 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "August-18 train timetable change". Greater Auckland. 31 July 2018. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "Timetables". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "The Onehunga Line Change". Greater Auckland. 20 June 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ "Timetable". Te Huia. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Hamilton's Te Huia train service to resume with new stop connecting to Auckland Airport". Newshub. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Pukekohe Station Closure". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Transport, Auckland. "Supporting growth in the south". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ Electric train lines may reach Hamilton – The New Zealand Herald, Thursday 28 February 2008

- ^ "Introducing Regional Rapid Rail – Greater Auckland". Greater Auckland. 17 August 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ "Auckland Council threaten KiwiRail with Environment Court action". Stuff.co.nz. 28 November 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- ^ "Rail proposal that Minister's office tried to block released". Radio New Zealand. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Rudman, Brian (11 July 2007). "Brian Rudman: Hallelujah, talk before bulldozers". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Jane Paterson (29 January 2020). "Govt's $12b infrastructure spend: Rail, roads and DHBs the big winners". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Niall, Todd (1 February 2022). "Auckland rail: 23 new commuter trains, costing $330m, take city fleet to 95". www.stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Waitemata ferries remembered at Devonport Library". timespanner.blogspot.co.nz. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ a b Council, Auckland (N. Z. ). (July 2011). North Shore Heritage – Thematic Review Report (PDF). Auckland City Council. ISBN 978-1-927169-23-0.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Captain magazine, summer 2015". Issuu. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "New Zealand Maritime Index from NZNMM". nzmaritimeindex.org.nz. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ Brlan Baxter, Fergus Gammie (1988). "Review of NZ Passenger Licensing System" (PDF).

- ^ Pedersen, Roy (1 September 2013). Who Pays the Ferryman?. Birlinn. ISBN 9780857906038.

- ^ Butler, Michael. "Omnibus Society - Hino RB145 buses". omnibus.org.nz. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "Our History". FullersFerries. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- ^ "'Absolute mess': Questions over $351m Auckland ferry deal despite cancelled services". NZ Herald. 13 April 2024. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Stuff". www.stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Transport, Auckland. "Auckland's first electric ferry is on track to be on the water in 2024". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Stuff". www.stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ "Belaire Ferries".

- ^ "Tiritiri Matangi Island Ferry Service".

- ^ Transport, Auckland. "Ferry good news: Auckland Transport announces Explore Group will operate Bayswater, and Birkenhead / Te Onewa Northcote Point ferry routes". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "Integrated ticketing". Region Wide. Auckland Regional Council. July 2010. p. 3.

- ^ a b Dearnaley, Mathew (24 December 2010). "$1m budget to help publicise Hop Card". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ "Start of Construction For Integrated Ticketing". Press Release, Auckland Transport. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Planned bus roll-out schedule". Auckland Transport. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ^ "Fare zones & calculating how much you pay". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "National Ticketing Solution | Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency". www.nzta.govt.nz. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Transport, Auckland. "Swipe right on public transport! PayWave, Google Pay and Apple Pay coming soon". Auckland Transport. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ a b "More ways to pay for public transport in Tamaki Makaurau Auckland". Auckland Transport. 30 April 2024. Retrieved 10 August 2024.

- ^ "Greater Auckland". Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "The Campaign For Better Transport". Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ^ "Public Transport Users Association of New Zealand". Retrieved 30 September 2018.

External links

[edit]- Auckland Transport (website of the region's local government transport body)

- Auckland Metro rail KiwiRail projects page

- Wheel Traffic (Tramways etc) in Cyclopaedia of New Zealand Volume II (Auckland) of 1902

- Photos of Downtown Municipal Transport Centre (now Waitematā) in 1940s to 1970s